In many discussions on intellectual property, open source, and digital economics, “piracy” is invoked as a looming bogeyman: it is said to destroy sales, starve creators, and hollow out entire industries. Yet the reality is far more subtle, and often more uncomfortable, than slogans allow. In this article, I want to walk through several underappreciated angles: a contentious EU-commissioned study that failed to show robust evidence of piracy harming sales; how digital “ownership” today is in many cases just a limited license; how companies like Nintendo respond with ever-stricter control; the peculiar Swiss legal paradigm of relaxed private use; and the shortcomings of equating every illegal download with a lost sale.

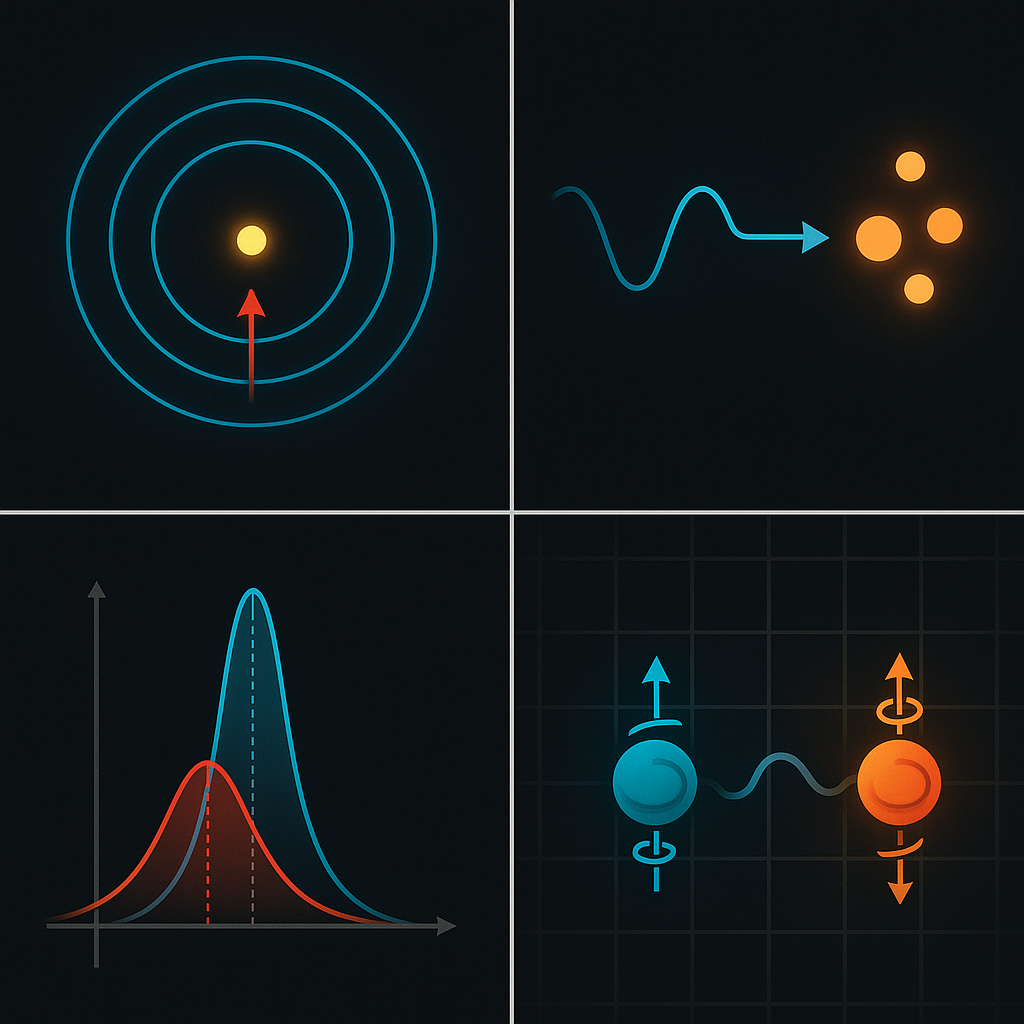

The EU-“hidden” study: no robust displacement effect?

One of the more surprising revelations in policy and digital-rights circles is that the European Commission itself once commissioned a large empirical study on how online copyright infringement (piracy) affects legal consumption, and then, for years, never fully published it. Eventually a version surfaced via freedom-of-information advocacy, sparking controversy and debate.

The core takeaway: the study did not find robust statistical evidence that piracy displaces legal sales in general. In other words, the analysis was unable to reliably conclude that piracy reduces sales across the board. The report did note limited exceptions, notably, among “recent top films,” piracy seemed to show a displacement rate of about 40% (i.e. 4 illegal views correspond to 1 fewer legal one), which they estimated would translate to a ~5 % loss in sales in that narrow category.

Crucially, though, the part of the study dealing with music, books, and games did not find a consistent or significant negative impact of piracy on legal sales. In fact, for video games, the study even observed a slight positive correlation: illegal consumption sometimes coincided with increased legal consumption.

It’s worth stressing a caveat: failure to find statistically significant displacement is not proof that piracy never harms legal sales , many dynamics are hard to measure, counterfactuals are fraught, and “lost sales” is a tricky counterfactual. But the study undermines the blanket narrative that piracy is always, or necessarily, a devastating drain on creators’ revenue.

Some observers believe the Commission’s reluctance to widely publicize the full findings was politically motivated: the portions that suggested weak displacement or even a positive effect for games were less compatible with a political push for stricter copyright enforcement. Regardless of motives, the episode reminds us that policy debates often start with assumptions rather than nuanced data.

“Buying” a digital game? No, you’re licensing it

Even in the absence of piracy, the landscape of digital content has evolved in a way that subtly shifts the consumer’s relationship to ownership. In many modern digital platforms, games, software, ebooks, streaming, “buying” no longer means fully owning in perpetuity; it means acquiring a license with usage constraints.

When you purchase a game on Steam, the Nintendo eShop, Microsoft’s Store, or Epic, you typically acquire the right to run or access that piece of content under certain terms (platform restrictions, DRM, server-dependence, revocation clauses, or region locks). You rarely (if ever) own a fully independent, transferable copy in all respects. The platform or publisher retains a degree of control.

This licensing model has multiple consequences:

- The publisher can revoke, suspend, or disable access (for example, if DRM servers shut down, or if account bans occur).

- The platform can impose region restrictions (you might not be able to play in a different country).

- Backups, resales, modifications, or transfers may be forbidden or blocked.

- Even playing offline can be contingent on periodic license renewals or authentication.

That shift means the notion of “piracy” itself becomes fuzzier: when I download a cracked version of a game, am I just bypassing the license enforcement? From a moral or legal standpoint the answer is typically yes, but consumers often reason that they’re not “taking away a sale” if their purchase would not have been possible under the licensing terms.

In effect, the “all or nothing” framing, “you can own it legally, or you must pirate it”, collapses under scrutiny. Many users pirate because they perceive the licensing restrictions or pricing as unfair, or because barriers (regions, platform compatibility) block legal purchase in their country.

Nintendo’s approach: tightening the perimeter

Nintendo, a longstanding and protective player in the gaming industry, offers a case study in how a company responds to digital control pressure.

- Intellectual Property Enforcement Program. Nintendo maintains a formal IP Enforcement program, where it seeks to remove unauthorized copies, block circumvention tools and software, and pursue counterfeits.

- Legal suits against hosting / file-sharing platforms. In 2025, a French court found that the file-sharing site 1fichier.com was liable for failure to block or remove unauthorized Nintendo game copies.

- Anti-circumvention / DRM pressure. Nintendo has long made it difficult to run unauthorized or modified cartridges or cartridges with hacks; they pursue “circumvention devices,” homebrew exploiters, and modifications of their consoles.

- Account enforcement, regional control, and digital “bundling.” Nintendo’s digital games are tied to user accounts and regional ecosystems, constraining resale, cross-region sharing, and transfer. They can also delist or disable games, especially older CDN or server-based features, making access contingent on Nintendo’s continued support.

In short, Nintendo defends its perimeter by combining legal actions, technical controls, and licensing architectures to limit how users can divert or resell access.

Switzerland’s “relaxed” private use paradigm

Switzerland occupies a curious place in European copyright discourse: historically, its law has allowed private copying for personal use (even when the work is illegally distributed) under certain conditions.

Under Swiss law, copying or downloading a work for one’s own private use (i.e. within a private sphere) is permitted, even if the original source was illegally uploaded, so long as the work is published, and provided no further distribution (upload) is involved. This is a stronger private-use exception than in many neighboring jurisdictions. In effect, personal consumption of illicitly-sourced content is tolerated under the law (again, so long as one doesn’t act as a distributor).

However: downloading software and games remains more contentious, because games often embed executable code (i.e. they straddle copyright and software law). Under Swiss law, unauthorized downloading or copying of computer programs is generally prohibited even for private use. The new Swiss copyright reforms of 2019 reinforced this distinction: the law continues not to criminalize private, noncommercial downloading of films or music, but explicitly did not legalize downloads of software or games.

This mixed regime creates a kind of legal gray zone. For music, movies, e-books, copying for private consumption is tolerated; for games, less so. The rationale is partly practical (hard to police) and partly normative (software is traditionally given stricter protection). But the broader principle remains: in Switzerland, an end user is not necessarily breaking the law by consuming a downloaded film or song in a private setting so long as no upload or commercial exploitation occurs.

For policy watchers, Switzerland’s stance is instructive: it acknowledges the difficulty of policing private consumption, and shifts enforcement focus from users to hosting services or distributors.

Why people pirate, beyond “stealing from creators”

One of the persistent fallacies in policing narratives is the assumption that every illegal download equals a lost sale. That is a naive and analytically suspect equation. In reality, people pirate for many reasons, some economic, some circumstantial, some political. Here are a few common categories:

- Affordability / limited means. Not everyone can afford full retail prices. Young users, people in lower-income brackets or in developing regions, or those with tight budgets may resort to piracy simply because paying is beyond reach.

- Unavailability / region restrictions. In many countries, certain games, movies, or ebooks are never released (or are released much later), or are artificially region-locked or geo-blocked. A consumer might pirate because the content is inaccessible in their jurisdiction even though they would be willing to pay if legally possible.

- Platform or format incompatibility. Perhaps the legal version is locked to an OS or platform the user does not have (e.g. the game is only on console, or only on Windows). Or it requires hardware or regional constraints the user cannot satisfy.

- Trial or “try before you buy.” Some users pirate with the intention of evaluating whether a game is worth purchasing, particularly when no free demo is available. If the game proves compelling, they may then purchase a legal copy.

- Ease, friction, or poor user experience. Sometimes the legal access route is so cumbersome (high DRM, poor distribution platforms, forced VPNs, huge patches, mandatory always-online checks) that piracy offers a frictionless alternative. The user’s calculation is: “If the legal version gives me trouble, I’ll bypass it.”

- Cultural or political resistance. Some users object to monopolistic platforms, heavy DRM, or restrictive license terms. Piracy, in their view, is a protest or assertion of digital freedom.

Because motivations vary, we can’t simply aggregate all piracy into a single “damage number.” It is misleading to assume each download was formerly a legal sale.

Misleading lawsuits: equating each download with a lost sale

Over the years, rights holders, especially in music and film, have pursued lawsuits or mass demand letters that treat every download as a lost sale, often seeking statutory damages far in excess of hypothetical lost revenue. Such approaches frequently rest on the assumption (or rhetorical convenience) that every unauthorized copy was once a potential paying customer. That assumption is deeply questionable.

For example, in the music industry, record labels have pursued individual users for infringement demanding high penalties, despite the fact that many infringers would not have bought the music legally anyway. These legal strategies bake in the “one download = one lost unit” fallacy.

In the video game world, similar lawsuits sometimes target servers, ROM sites, or emulators, assuming that every pirated copy displaces a sale. But many users who pirate might never have bought the game under licensing constraints, or would only purchase a subset. Some game creators, ironically, even tolerate emulation as a way to build community interest (though that’s a delicate balance).

A more meaningful approach would distinguish between substitution (someone pirated instead of buying) and complementarity or exposure (someone pirated, then later bought). Unfortunately, many lawsuits and demand models simplify the math to the detriment of nuance.

Rethinking “piracy = harm” in a nuanced digital world

Given all of the above, how should we rethink piracy in the modern digital economy? Below are several reflections and potential pathways:

- Recognize that “lost sales” is a rough construct, not a direct ledger entry. Not every download represents a lost revenue unit; many are exploratory consumption or would not convert.

- Focus enforcement on distribution infrastructure, not individual consumers. Switzerland’s model of tolerating private consumption while targeting hosting services is a pragmatic example of aligning enforcement with enforceable scale.

- Lower friction, expand access, and adopt fair pricing. A powerful lever is to improve legal access: more regional releases, pricing adjusted to local means, fewer region locks, better cross-platform compatibility. When legal access is easy, many users will prefer it over piracy.

- Rethink the licensing model. Allowing resale, transfers, or more consumer freedoms may undercut piracy’s appeal. If a user feels they truly “own” what they pay for, they are less tempted to pirat, or may see an upgrade path.

- Distinguish between content types and lifecycle. Top blockbuster films may suffer some displacement. Niche, indie, long-tail content might derive more benefit from exposure. Blanket policies rarely fit all.

- Better measurement and transparency. We need more open studies, not suppressed reports, so that policy debates rest on robust evidence, not faith or rhetoric.

Conclusion: toward a more balanced approach

Online piracy is not a binary moral failing, nor is it always or directly a direct tax on creators. The digital era has complicated the definitions of ownership, access, and displacement. The suppressed EU study reminds us that even large institutions sometimes confront inconvenient null results. Nintendo’s aggressive controls show how companies attempt to defend perimeter fences in this shifting terrain. And Switzerland’s relatively permissive private-use rule underscores a different pragmatic posture in balancing rights enforcement.

For creators, platforms, policymakers, and consumers, I’d argue the task is less to demonize piracy wholesale than to understand it, reform the conditions that drive it, and to craft sustainable business models and legal regimes that adapt to the realities of digital distribution.