For more than a century, photography has carried a powerful cultural weight: the idea that when we look at a photograph, we are seeing reality. The act of pressing a shutter was supposed to freeze a moment in time, preserving a scene just as it appeared. But in the digital age, and especially in the AI-driven era of smartphone cameras, that assumption is coming undone.

Today, the “photos” in your camera roll may not be straightforward captures of light and shadow. Increasingly, they are stitched together, sharpened, filled in, and in some cases outright reimagined by artificial intelligence. What you see might look real, but reality itself is no longer guaranteed.

The Samsung Moon Example

In early 2023, a controversy broke out over Samsung’s “Space Zoom” feature. Users began sharing side-by-side shots of the moon taken with Samsung phones. The results were astonishing, sharp, detailed lunar surfaces with craters and ridges far beyond what the camera’s small sensor and optics should reasonably be able to resolve.

Tech bloggers and independent testers dug deeper. Some experiments revealed that Samsung’s algorithms weren’t just enlarging existing data, they were recognizing the moon and overlaying it with AI-generated details. In other words, the moon photo wasn’t entirely your moon photo. It was partly Samsung’s moon, reconstructed from training data and computational assumptions.

Samsung defended the feature, claiming that it wasn’t “fake” but rather an enhancement that leveraged AI to reduce blur and fill in missing detail. Yet the debate was unavoidable: if the pixels weren’t captured in that exact moment, was the photo still a record of reality, or was it, at least in part, a fabrication?

The Rise of Computational Photography

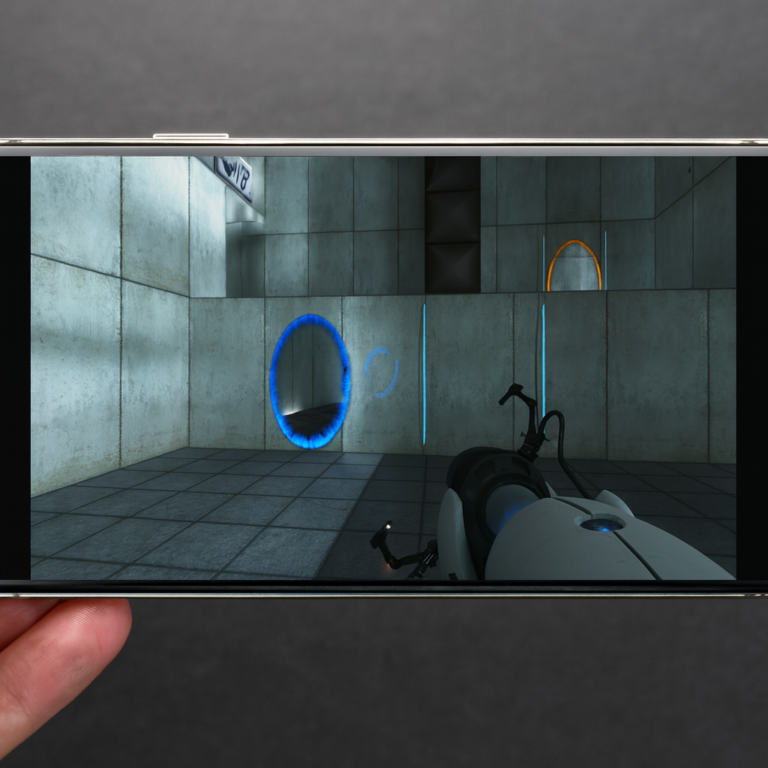

Samsung is far from alone. Google, with its Pixel Pro series, has staked much of its marketing on computational photography. The company’s “Super Res Zoom” and newer “Pro-Res Zoom” don’t rely on traditional optical magnification. Instead, they use a cocktail of multi-frame image fusion, machine learning upscaling, and prediction models to construct images sharper than the sensor itself can capture.

The effect is magical. Photos of distant buildings, birds, or landscapes appear pin-sharp, even when taken with lenses that would normally blur out fine detail. Google insists the process is grounded in real sensor data, combining multiple exposures, correcting for hand shake, and enhancing the result. Still, the line between enhancement and invention is getting thinner by the year.

It’s not just zoom, either. Night photography on modern smartphones often involves taking dozens of exposures over several seconds, merging them, correcting color, and sometimes even painting in stars that weren’t visible to the human eye. Portrait modes blur backgrounds to simulate expensive DSLR lenses. Skin tones are balanced, shadows lifted, eyes sharpened. Each step moves further from the raw moment.

When Does Enhancement Become Fabrication?

The central question is deceptively simple: when does a photograph stop being a photograph?

For some, any computational adjustment beyond basic color correction feels like a violation of photography’s documentary roots. A smartphone moon shot that inserts crater textures from a machine learning model is, in their eyes, no longer a photo of that moon on that night.

Others argue that photography has always been about interpretation. Darkroom techniques manipulated exposure. Film stock shifted colors. Wide-angle lenses distorted perspectives. Even in analog days, photography was never a neutral capture, it was an art shaped by technology. By that logic, today’s computational methods are just the latest step in a long tradition of technical enhancement.

But there is a difference in degree. When AI invents details that weren’t present, photography begins to edge toward something new, an image that feels photographic but may not be tethered to reality.

The Stakes: Journalism, Memory, and Trust

This debate isn’t just academic. For photojournalism, where images serve as evidence of events, the stakes are high. If algorithms can hallucinate detail, can we still trust photographs as proof? A protest photo, a crime scene, or a historic moment could be subtly altered by automated processing, without the photographer even realizing it.

For everyday users, the issue is more personal. Family snapshots and travel photos are supposed to preserve memories. If AI is “improving” those memories by adding skies that weren’t as blue, stars that weren’t as bright, or faces that didn’t look exactly that way, are we still remembering the moment, or a computer’s curated version of it?

Questions That Won’t Go Away

As AI becomes inseparable from consumer photography, the questions get sharper:

- If a smartphone fills in missing detail with AI, is the final product still a photograph or a digital illustration?

- Should cameras disclose when images are algorithmically enhanced, or even offer “authentic capture” modes for unprocessed reality?

- Will society need new categories to distinguish between photography-as-documentation and photography-as-artifice?

- At what point do we risk losing touch with the very subjects photography was meant to preserve?

The Future of the Medium

There’s little doubt that computational photography will continue to advance. The market rewards it: people want photos that look stunning, regardless of whether they are technically authentic. Google and Samsung aren’t competing to replicate reality, they’re competing to generate the most pleasing, shareable image.

But perhaps the future of photography won’t be about rejecting AI, but about transparency. Just as we distinguish between raw footage and edited film, we may need to distinguish between “captured” photos and “processed” ones. Journalists may demand sensor-only modes; artists may embrace AI composites as a new canvas.

What’s clear is that photography is no longer a straightforward window into reality. It has become a negotiation between light, sensor, and machine learning.

And that leads us back to the fundamental question: if photography no longer guarantees reality, then what is it really for?